Your Phone Was Picked Up by More Than 100 People Before You

February 9, 2023

Peg: “What is this?”

Birdie: “An email from the Sweetie Pants contractor 2 years ago.”

Peg: “‘Ms. Jay, I am writing to inform you that the proposed Bangladesh factory is notoriously one of the world’s biggest sweatshops. Please advise’…And then you replied, ‘Sounds perfect, thanks!’…Please tell me you did not think sweatshops are where they make sweatpants.”

[Clip]

I was watching the movie Glass Onion with 6 other teens when we came across this scene. I was a bit shocked, as I too thought that sweatshops were shops where you bought sweatpants. I turned to my friend and whispered, “What’s a sweatshop?” and was surprised when no one else was asking the same question.

It wasn’t until we had to pause the movie that I got my answer. I asked again and one of my other friends replied, “It’s like a factory.” My first friend answered, “You remember Lyddie?” I nodded. “It’s like that. My eyes widened as I realized what she meant.

Lyddie is a book about a young teenage girl from the late 1800s who gets separated from her family to work as an indentured servant in a textile mill. The air was polluted and humid, and she would have to work for over fourteen hours a day.

If you’ve watched the movie Enola Holmes 2, or perhaps read the book Iqbal, you may be familiar with this term. Sweatshops were used a great deal back in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t still used anymore. Many modernized versions of these health-attacking workplaces exist today, especially in countries where large populations aren’t able to find a high-paying job they are accepted for. These countries include Bangladesh, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, China, and many more–including the US Sweatshops can be found in the greatly populated areas of the US such as LA or NYC, where immigrants are specifically targeted due to many desperately looking for a job to be able to take care of their families in a new country.

Why are they bad?

The harsh working conditions and the low wages are what make these factories looked down upon. Many of these workers have to work for well over 10 hours a day, 7 days a week in congested spaces where disease can quickly and easily spread. These spaces are many times dirty or poorly ventilated leading to high or low temperatures. There have been many cases of abuse–physically, sexually, and verbally–that have been documented.

Not only are there adult workers, but child labor is common in sweatshops. Children at the age of 6 have been found working for 16 hours a day. As they are children, they are less likely to stand up against older employers, causing them to be more easily taken advantage of. When the inspectors come to make reports on these factories, they may notify the employer ahead of time, which gives the employer the opportunity to hide their child workers and clean up the workplace a bit before the inspector’s arrival. In some cases, the inspectors or the police are even bribed to look the other way, which can lead to workers losing the remaining hope they have for a brighter future.

Dejian Zeng, an NYU grad student, went undercover to work at an Apple sweatshop in Shanghai for his project. Insider Tech interviewed him 5 years ago about his experience. He spoke of how boring it was to be doing the same job for 10 hours straight, six days a week, and how full the factory was, with over 70,000 workers who were employed there. He was paid $450 a month, which “included the base salary and the overtime wages.” The Week goes more into producing Apple products by listing many shocking statistics.

According to The World Counts, the pay workers in sweatshops receive can go as low as “20 cents per day or about one cent per hour.” Otherwise, workers are paid by item. For example, Garment Worker Center shares that, “Approximately 85% of garment workers do not earn the minimum wage and are instead paid a piece rate of between 2-6 cents per piece.” Many workers choose to work for longer hours because of this system–they want to make as much as they can in a day. One problem with sweatshop worker pay is that their employers may even go to the extremes of taking away pay as a punishment, or without the knowledge of the worker.

Why do sweatshops continue to get workers? It’s because of the number of people who need the money. Children and young adults are sent to work in sweatshops to help earn money for their families who are struggling with debt or to be able to pay for basic needs. The cycle of sweatshops continues as workers are underpaid so much that some aren’t able to pay for life’s price. It also continues as children are sent to work when they could be going to school and studying to be eligible for higher-paying, safer jobs leading them to grow up and do the same to their own children. Which was the case for 15-year-old Bhiti in Bangladesh.

Bhiti’s mother, Feroza, had sent Bhiti to a garment factory at the age of 12. For three years she had been working there, tirelessly, day after day, doing the same job–sewing pockets into jeans she would never be able to buy herself. Feroza had fallen under the same fate decades before, and when food was harder to bring onto the table, Feroza decided to send her eldest daughters off to work as well.

How Do Sweatshops Connect To Me?

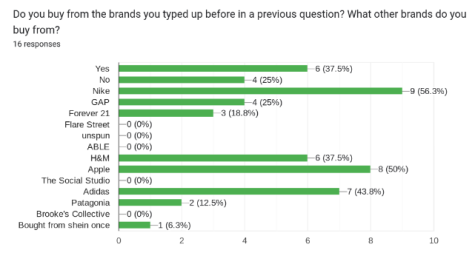

Many of the brands you buy from at the mall use sweatshops to produce their items. A great percentage of these sweatshop brands are clothing brands such as Nike, Gap, Forever 21, H&M, Adidas… the list could go on and on. Even the whimsical Walt Disney Company has been reported to use sweatshops. It was incredibly hard to find a popular brand that didn’t use sweatshops as many of these brands have either been reported to use cheap labor or aren’t transparent enough when sharing their policies and worker wages. The only one I could find–out of many other non-sweatshop brands–was Patagonia.

The items we buy from each of these stores have been imported from across the world, many times being produced in sweatshops. Big brands such as Walmart or Mattel hire factories to produce their products. The factories hire workers to produce the products on a massive scale. These products are packaged and sent to the big brands for them to distribute and sell through their stores for customers to buy.

Now don’t feel bad, it’s not entirely our fault. We buy from these companies because either we like their products or they have prices in our price range. But our choices do make an impact. If we collectively as a group lower the number of times we buy from these companies, or even just acknowledge the existence of sweatshops and the issue it is, we can change the perspectives of others and potentially get the higher-ups to fix their problems.

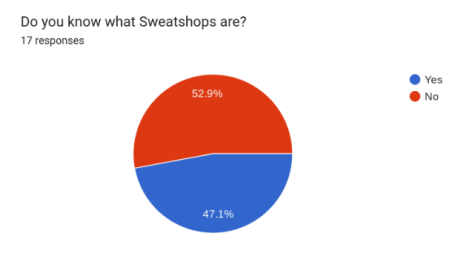

It’s important to know what a sweatshop is to know how sweatshops connect to you. Out of 17 respondents, 52.9% did not know or were unsure about what sweatshops were. This is a problem as the mere existence of sweatshops is a major issue that affects the whole world. Knowing the problem and acknowledging that the problem exists is the first step to preventing the problem from occurring. Spreading awareness is a way to bring attention to this issue which could cause higher-positioned people to make a change for the better.

It’s important to know what a sweatshop is to know how sweatshops connect to you. Out of 17 respondents, 52.9% did not know or were unsure about what sweatshops were. This is a problem as the mere existence of sweatshops is a major issue that affects the whole world. Knowing the problem and acknowledging that the problem exists is the first step to preventing the problem from occurring. Spreading awareness is a way to bring attention to this issue which could cause higher-positioned people to make a change for the better.

Another solution–a more direct one–is buying from alternative brands. A great site to find similar clothing brands that practice more ethical behaviors is Good On You. Their staff writes ratings and reviews based on how ethical (People, Planet, Animals) a fashion brand is. What makes the site even cooler is that they have a price-ranging system and when you search for an unethical brand, it suggests similar brands that are ethical. It’s a very useful tool.

Even though sweatshops bring many jobs for those who need it, change needs to be done to make sure workers are getting what they need and deserve.