Irish Gaelic: A Language Nearly Lost

March 13, 2023

Green Green Green

With Saint Patrick’s Day coming up and the month of March in full swing, Americanized notions of Irish themes are in everyone’s line of sight. Everything’s green and embellished with four-leaf clovers, pots of gold, and leprechauns. This time of year makes many who aren’t familiar with the culture curious about its origins, some even taking to Google with the question “What does Saint Patrick’s Day celebrate?” Many would be surprised to know that St. Paddy’s marks the death of Saint Patrick, the patron Saint of Ireland, but the holiday has largely evolved into a celebration of the Irish culture. The day is distinguished by parades, special foods, music, dancing, drinking, and of course, a whole lot of green. This is really the only Irish holiday widely recognized in the United States and has served to spark significant interest in Irish history and culture in many.

The Penal Laws

Many find themselves curious about the Irish language itself around this time of year, as it’s not commonly spoken in the United States. Individuals often take to the Internet to satisfy their curiosity and are usually shocked by what they find. The reason why the Irish language, or Irish Gaelic, is so rarely spoken in the U. S. today is due to its decline at its roots: its native speakers themselves. The decline in the use of Irish Gaelic began in late 19th century Europe when the Penal Laws were repealed. The Penal Laws were laws passed against Roman Catholics in Britain and Ireland after the Protestant Reformation. These laws penalized the practice of the Roman Catholic religion and imposed civil disabilities on these Catholics. According to Britannica, these laws “prescribed fines and imprisonment for participation in Catholic worship and severe penalties, including death, for Catholic priests who practiced their ministry in Britain or Ireland. Other laws barred Catholics from voting, holding public office, owning land, bringing religious items from Rome into Britain, publishing or selling Catholic primers, or teaching.” Due to a large portion of this religion being Irish Catholics, these Irish-speaking individuals were forced to assimilate into the dominant Protestant culture, and most Protestants spoke English. When the last of the Penal Laws were repealed by 1829, Irish Catholics were free to participate in society at a greater magnitude. Since this society was more molded to fit the average English Protestant, it was evident to many Irish-speaking Catholics that they would have better opportunities if they spoke English, causing a large decline in the commonality of speaking Gaelic.

The Potato Famine

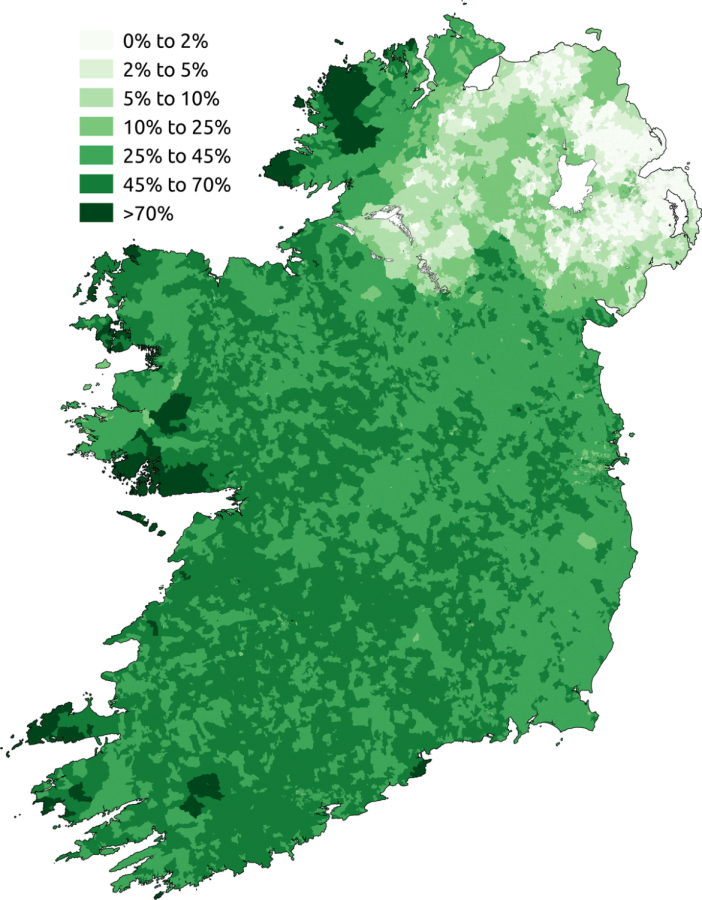

Another big blow to the Irish language happened as a result of the infamous Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s. The famine hit especially hard in the southern and western parts of Ireland, which were the more rural, less economically developed areas of the country. Here, more Irish people stuck to their Gaelic-speaking roots instead of adapting to the Protestant-dominated United Kingdom and learning English. When the potato blight hit, many of these farming communities died from starvation or disease. Those who were lucky were able to emigrate to other countries and therefore had to pick up a different, foreign language in their new home, lessening the amount of Irish Gaelic speakers significantly. A map showing the regions hit hardest by the famine lines up very similarly to a map showing where Irish was spoken the most in the country, so it’s no surprise the language continued to die out along with its native speakers.

Current Day

Today, both Irish and English are the official languages of the Republic of Ireland (which excludes Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom). Irish is still mainly spoken in the southern parts of the country, but it can be heard just about anywhere, from rural areas to bustling urban centers like Dublin. According to Ireland’s Central Statistics Office in April 2016, the percentage of people in Ireland (aged 3 and above) who could speak Irish was 39.8 percent of the country’s population. From this statistic, it is evident that the Irish language has not nearly met its complete demise, but its commonality has lessened significantly due to Ireland’s unfortunate history.