Trouble in paradise: the battle between loyalism and autonomy in New Caledonia

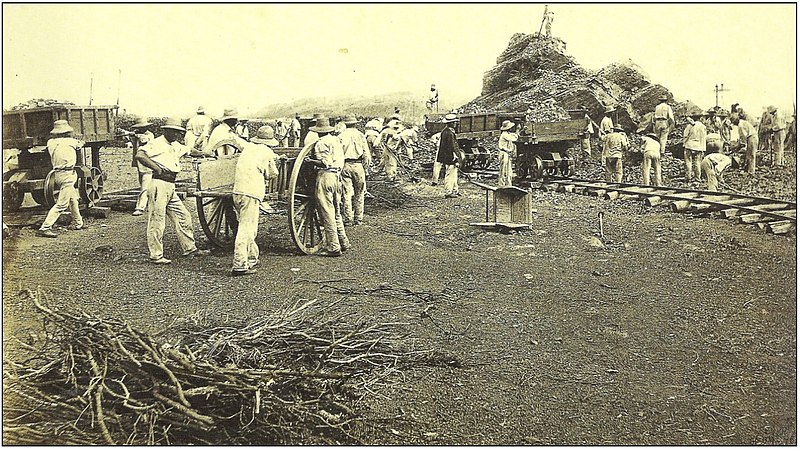

French prisoners clearing land as part of their sentences.

April 5, 2021

On an archipelago in the South Pacific, the city of Nouméa wakes up to a new day. The sun rises, illuminating the clear aquamarine waters typical of the South Pacific. Local vendors prepare their wares, selling food, souvenirs and local handicrafts along the white sand beach at the Anse Vata Bay. While this scene sounds idyllic, it is not. A few miles inland, at the Territorial Congress, a French flag and a Kanak indigenous flag line the entrance to the building. While they fly together for now, it is easy to detect an air of tension. The flags snap in the wind, almost competitively, wary of each other’s presence. However, this uneasy alliance has already lasted for more than 20 years. Both sides have grown weary, and the theme of change has increasingly been muttered, shouted, and graffitied throughout the island in recent years. When change does come to the islands, what implications will it hold for the South Pacific and France?

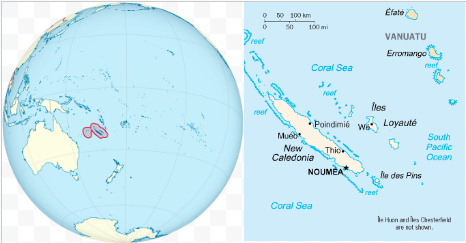

The islands in question are the overseas collectivity of New Caledonia, an archipelago 1000 miles east of Australian shores. Located in a region of the Pacific known as Melanesia, characterized by the dark skin tone of its inhabitants, New Caledonia stands out from many of its regional neighbors. Unlike many other island nations in the region, which have attained full sovereignty, New Caledonia remains a vestige of a European empire. Inhabited by the native Kanak people, New Caledonia was encountered by James Cook in 1774. Initially, Europe did not take an interest in the islands, owing to the reports of cannibalism by visiting merchants and explorers. By the mid 19th century, however, New Caledonia became part of a frantic power grab. As other Oceanian territories fell like dominoes to other European powers, France scrambled to take whatever was left of the region, hoping to profit from it as much as their competitors had. In 1853, the French tricolor was hoisted over the village of Balade, officially marking the annexation of New Caledonia.

It was only in 1864 did France start reaping the rewards of the islands. Seeing the success of the British model in Australia, the French government turned New Caledonia into a penal colony, transporting political prisoners, petty criminals, and war prisoners were transported en masse to the island. Colonial authorities wasted no time in using these settlers to exploit the islands. Shortly after, settlers had struck nickel underneath the ground. Seizing on the large market demand for nickel in currency and luxury goods, France further tightened its grip on the colony. Brush was cleared to make way for plantations, mines were excavated to find more nickel, and the Kanaks were forced onto reservations. In response to the exploitation of their land, several Kanak leaders banded together under the leadership of Chief Ataï in 1878, launching the first large-scale resistance (article in French, use Google Translate if necessary) against French authorities. French troops quickly crushed the rebellion, fearing the loss of their political and economic influence in Oceania. Such a move proved wise for France; during World War II, Allied troops used the islands as a staging ground to push back Japanese expansion into the Pacific, a crucial step in ending the global conflict.

By the 1970s, however, rumblings of an independence movement began arising again. In response to what they perceived as increasing French encroachment on native land, the Kanak community began demonstrating for political change. Within months, the movement began to coalesce around a central figure, the priest-turned-activist Jean-Marie Tjibaou (article in French, use Google Translate if necessary). Espousing an ideology known as Melanesian Socialism, which advocated for the restoration of traditional social and political values, Tjibaou quickly gained a following amongst his fellow Kanaks, who felt alienated by the capitalist system that had brought on the exploitation of their land. Shortly after, Tjibaou founded the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS), a political party that would give a centralized voice to his followers. Originally founded to peacefully and politically advocate for the self-determination of the Kanak people, FLNKS soon turned into a militant group, against the wishes of Tjibaou. An insurgency soon emerged, which would drastically change the political course of the islands.

Throughout the 1980s, violence plagued the islands. Militants frequently clashed with police in the streets, and ethnic riots between pro-independence Kanaks and loyalist white New Caledonians (known as Caldoches) were a common sight throughout the islands. In May 1988, the violence finally reached a crescendo with the Ouvéa Hostage Crisis. On the island of Ouvéa, a few miles off the coast of the main island, militants attacked a police station, taking hostage 27 gendarmes (police officers) in an isolated cave. After negotiations stalled, French President Mitterand deployed GIGN Special Forces to rescue the hostages by force, at a cost of two special forces agents and 19 FLNKS militants. The crisis caused a huge outcry in New Caledonia, with Kanak leaders condemning the strong-armed tactics of the French government and Caldoches appalled by the actions of the militants. Fearing the impending risk of even more ethnic violence, political leaders rushed to hammer out a peace deal. In 1988, the Matignon Accords (article in French, use Google Translate if necessary) were signed in Paris, providing amnesty to the perpetrators of the hostage crisis and setting up a 10 year reconciliation and dialogue period, after which another deal was to be scheduled regarding self-determination. True to the Matignon Accords, another peace deal was signed in 1998. The Nouméa Accords provided the New Caledonia legislature with more administrative powers along with 3 chances to hold referendums regarding independence.

This brings us to today. Stability has more or less returned in the years following the Noumea Accords, though animosity still lingers over a complex assortment of issues, such as land use and economic inequality. Loyalists cite the integral role France plays in the development and security of the islands; with €1.3 billion ($1.5 billion) in subsidies coming from Paris each year, many fear that the islands will not thrive if this vital link is cut. In addition, as China continues to expand aggressively into the Pacific, many worry that independence (and the subsequent loss of French military protection) would entail a submission to Chinese neocolonialism. On the other hand, independentists cite historical and socio-economic problems that exist on the islands, one of them being a key reminder of their colonial past. To this day, nickel exploitation remains one of the largest industries; as of 2020, New Caledonia is the 4th largest producer of nickel in the world, producing nearly 200,000 metric tons of the mineral per year. The magnitude of the nickel mining has raised environmental and social concerns, reigniting Kanak demands for autonomy. In 2014, a chemical spill occurred at a processing plant, polluting a local river and sparking days of protest by the local Kanak community. While the spirited concerns of each side threaten a resurgence of social unrest, New Caledonians have now taken to the ballot boxes to air their grievances. In 2018 and 2020, independence referendums were held, in accordance with the Nouméa Accord. In both instances, independence was narrowly rejected, primarily along ethnic lines. However, a notable trend must be pointed out; between the two successive referendums, the independence vote grew in size, and Kanaks who had boycotted the vote in 2018 took part in the 2020 vote. The third and final vote will possibly be held in 2022, and no matter what the result, it is clear New Caledonia will have to do some political soul-searching after the vote.